Five Years Later

Today's the five year anniversary of Necrobarista's release. For those unfamiliar, a quick primer: Necrobarista is a 3D visual novel set in a cafe that sits on the boundary between the real world and the afterlife, acting as a place for the recently departed to stop for one last cup of coffee. It was developed by a team of less than a dozen people mostly based in Melbourne, Australia, though there were a small number of personnel, such as myself, who worked remotely. It shipped on three platforms and in fourteen languages, was generally well received, and won a couple of awards. It was first released on July 17, 2020 (Apple Arcade), followed by a PC launch on July 22 and an expanded "director's cut", dubbed Final Pour, released for existing platforms and Nintendo Switch in August 2021. I was the lead writer.

So, where to begin?

I think I need to start here, not with a disclaimer, but to set the tone: Necrobarista's development was extremely difficult. As a consequence of many confounding factors, including a large number of poor choices by management spanning across the game's development, we were underpaid, underresourced, and a year before release, the game was content complete but we were running on fumes. The studio environment always had toxic elements, and they only intensified once the Covid lockdowns began. People I care about were hurt by this. I was hurt by this! I walked away hurt, and I am still hurt.

I suppose it's appropriate, in the end, that Necrobarista itself is a story about complex love, with confounding factors.

The arrogance of youth!

It's funny to think about where I was when I started work on Necrobarista, both as a person and as a professional. I was asked to work on it after giving some respectful but pointed feedback on its PAX Aus demo (2017). The personal context around this is that I was about to finish working at a studio where I had been required to be subordinate to a deeply abusive creative who was completely new to working on games, and who was intentionally ignorant of the realities of production that constrain a game's writing. Just a complete dilettante in every way. Though the studio's management readily admitted that they had made serious errors in allowing him to repeatedly attempt to gaslight myself and other professionals at the studio about the process of developing a game with no negative repercussions, this experience was nonetheless extremely difficult and left me with a bunch of mental trauma and related health issues, including memory and heart problems. Game development, everyone!

So, I was very burnt out from my previous experiences (both recent and not-so-recent) but very sure—perhaps arrogantly!—of my ability to write a good story for the game, and extremely motivated to prove myself to my industry peers. This has historically been a reason behind me overcompensating on various things, and Necrobarista brought that out in a number of ways.

I've spoken before on how I found the creative process on Necrobarista an extractive one. It was extremely important to the game's director to evoke emotion, as much as possible, to create a deeply memorable experience. Thus, it was top priority for the rest of us, and something we all had on our minds, constantly - especially me. So I would leave the house every day to work in every late-night cafe I could find, put on a playlist of sad music about loss and death, and work to untangle it all. It's abundantly clear now that I was not experienced enough or mature enough to undergo that creative process in a sustainable way, but since everyone else on the team was burning the candle at both ends (or worse), I saw no issue with how I approached it. Having worked on projects since then that were actually well-managed, I've learned to pace myself better.

An important thing to understand about Necrobarista's script is that it was essentially implemented into the game as each successive part of the script was finished. When I joined the team, they had worked through several prototypes and attempts at building a larger narrative, but had so far been unsuccessful. This, combined with the studio's dwindling (or outright lack of...?) funds, put me under a significant time crunch. So, the process of writing was a rapid one. It went a bit like this:

- Before I started, I read through all the existing material to see what could be saved or otherwise repurposed. I chose to keep the broad concepts for the characters intact, for example, and the "knife fight" sequence from the existing demo had already been scored and animated, so I shaped my work around retaining it.

- This was a multifaceted creative choice: I was joining late into the creative process on a project that had been going for years, so it wouldn't serve me well to rock the boat by throwing away perfectly good ideas that people were creatively invested in. And, of course, I was ostensibly working to a short timeline, so it made sense from a production standpoint as well.

- For reasons of convenience and also the above, I stayed fairly close to the established writing and dialogue style (elevated, snappy, quippy) from the studio's previous prototypes. There was no time or good enough reason to move away from that.

- Extremely fun(ny) fact: one member of the team had a huge problem with me making Maddy bisexual! This is the one axe I will happily grind in this post. Extremely laughable and embarrassing, and I am doing this person a favour by not naming them.

- I was validated in my choice by many lesbians. Shoutout to lesbians 👍

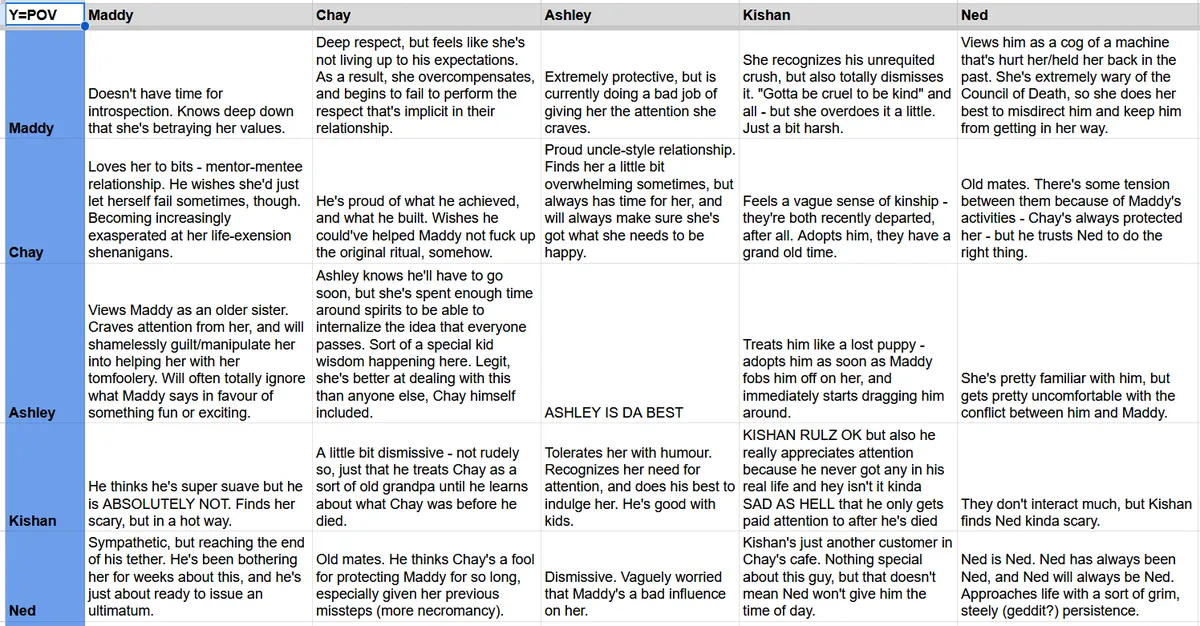

- I built a matrix of character relationships to make sure the cast was interacting with each other in unique ways.

- I also consulted closely with the team to see which environments we were retaining from the studio's previous attempts. The interior of the cafe is pretty similar to the PAX 2017 demo, for example, and there are a bunch of elements from other prototypes that were repurposed for things like the cafe's exterior.

- The director made me watch a ton of anime that the team was heavily referencing, either visually or thematically. Some of it I liked, some of it I... didn't, so much. There were a couple of episodes of Bakemonogatari he showed me which were a bit odd, but I really didn't like Time of Eve, one of their biggest touchpoints. Not to my taste, but it was still a big influence on Necrobarista's story and setting. Anyone familiar with it will see the homage.

- Other big contemporary influences: Nier: Automata (more on that later), Night in the Woods, Kentucky Route Zero, VA-11 HALL-A (unsurprisingly). Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex was also a touchpoint for some specific elements - the Ashling robots' strong personalities draw heavily from the Tachikomas, for example.

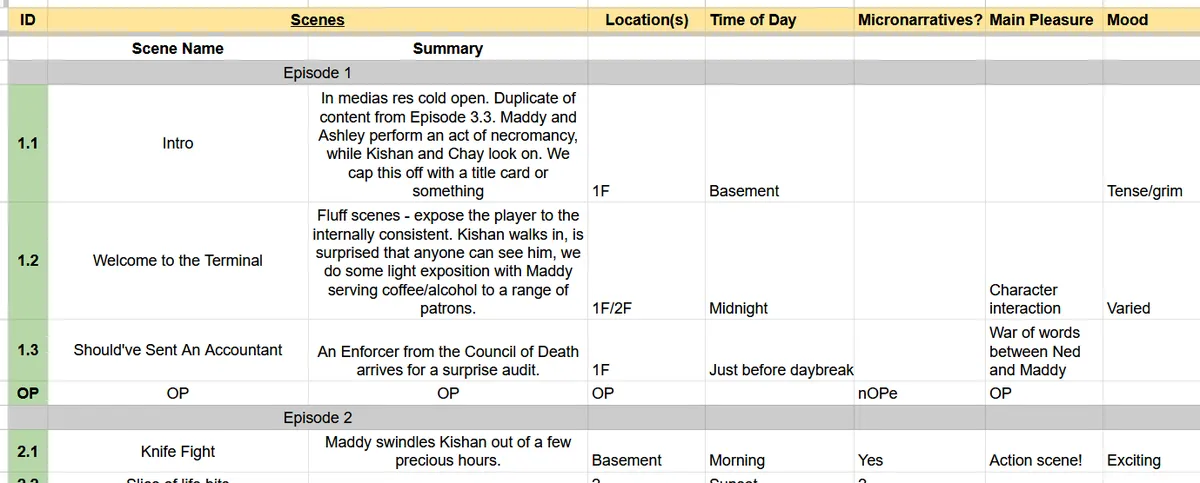

- Somewhere in the middle of all this, I rapidly threw together a story outline. I don't remember whose idea it was (maybe mine!), but I went for a four-act structure along the lines of kishōtenketsu, though that ended up being a little muddled, since the final iteration of the main story was split into nine chapters with five (I think) interstitial sequences with the robots, as well as the additional DLC episodes which came out later, and which ended up having to be salvaged through almost complete rewrites for the director's cut...

- From then on, I was scriptwriting. We had a developmental editor giving high-level feedback, but I was otherwise free to write generally undisturbed.

- I did all my scriptwriting work in Google Docs, which I would not recommend for a large variety of reasons. The biggest one for me is probably the smallest one for everyone else, which is that our ingame dialogue font didn't have glyphs for "smart quote" characters, meaning that they were always very ugly. By the time I raised the alarm, everyone was too nervous about breaking the game to replace them with normal ones. A tragedy.

- Seriously, please, write in a spreadsheet at the very least.

- My absolute biggest priority in the script was hewing to the classic narrative design constraint of doing everything as cheaply as possible. If we could present a camera shot without any animation or showing characters' faces, that was how we did it. Every extra line of dialogue inside a shot meant that we had more room for narrative within our extremely limited budget.

- Balancing that constraint with the need to avoid being overly wordy was very tricky! That's a classic problem with developing visual novels, and Necrobarista being presented in full 3D added unfathomable amounts of complexity to that.

- The script was done, I think, around the middle of 2018. The studio ran playtests in early 2019. We made script adjustments and additions accordingly.

- That's a load-bearing paragraph.

- The vibe of the first playtests was, I'd say, "positive but befuddled". Some players struggled to follow the story. My solution was to add interstitial sequences between the chapters that were heavily inspired by the interstitial sequences in Nier: Automata where the pods discuss the narrative. This, of course, is not necessarily a Yoko Taro Original Narrative Innovation, but Nier executed it particularly well and it served us very well too. The sequences provided a ton of narrative glue and fit naturally. I'm proud of them!

- If you're going to liberally borrow, borrow from the best.

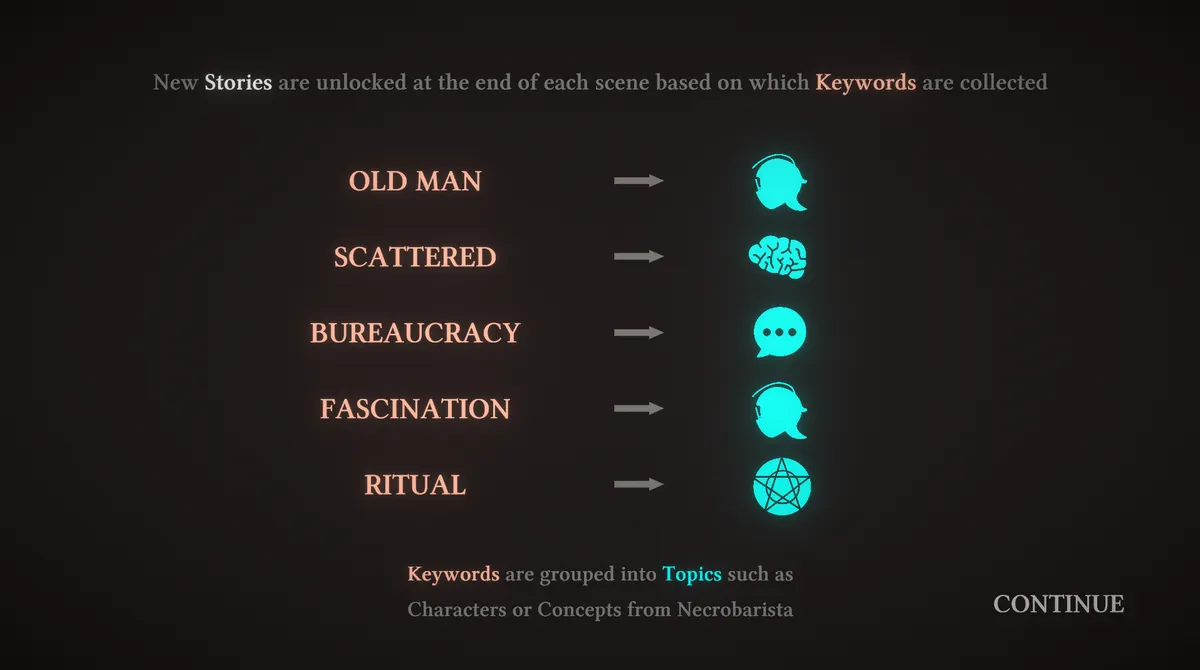

One problem that the playtests highlighted that was never really fixed, however, was the gameplay. I think it's fair to say that the actual game elements of Necrobarista never really worked. The game's director had a quixotic obsession with putting something videogamey between the chapters to differentiate it from a gameplay-less visual novel. That is a blinkered view of an incredibly diverse and underappreciated medium, to put it lightly, but it wasn't something I had control over or any input on, so I just had to live with the consequences.

Anyway, that was an ongoing problem. We would show the game to someone (or many someones), they would praise the story, and then they'd get stuck between chapters on the shoehorned-in gameplay. I'm working from distant memory here, but at one point you were forced to read the (extremely long and perhaps excessively verbose) side stories in their entirety to collect enough tokens to unlock the next chapter. It was fairly disastrous in terms of its effect on the pacing of the game and the player's attention span. These systems went through several iterations and I don't think they ever ended up being good. For me, anything that got in the way of the main story—the thing everyone was playing the game for!—was obviously Not Good, but it ultimately wasn't something I had influence over, even though I was ostensibly a "lead".

However, it is worth noting that this was emblematic of one of the biggest sources of rot within Necrobarista's development process: we were constantly redoing work. The director was an extreme perfectionist, and besides the script, which I was generally left alone on, everything was constantly being worked on for the sake of being worked on, past the point of absurdity. Camera shots, lighting, animations, gameplay, environment design, prop placement... none of it was safe. You can even see examples of this in shipped content - the original release version of the game has a significantly different visual style to the Final Pour version, which was completely re-lit. Anyone can see that was unnecessary labour. I don't think choosing to work on other things would have necessarily made the game better or worse, but I do think that by the time anyone was in a place to critique these processes, the burnout (inflicted by myriad internal and external sources) was so overwhelming that doing anything else would have felt apocalyptic.

And then, in mid-2019, we were content complete.

It's funny to think about that. I felt like we were ready to go. It felt like we had momentum. And then that all ground to a halt when an important development partner completely failed to deliver an extremely crucial deliverable. In fact, they didn't even start working on it, despite assuring us of constant progress. And all of a sudden, with the weight of a hundred terrible load-bearing choices crashing down on the team, it felt like it all went to absolute shit.

As shown in the intro, I wrote a portmortem for my own records in August 2021. But even that document doesn't really go into the year of development that led up to the game's eventual release in July 2020. There are many complexities that limit what I can speak on publicly in regards to the game's release, but I don't think it harms anyone to say that we did not know when the game would be able to go live until a week before its release. Games journalists who had been given review copies at the start of the year, or even earlier than that, were clearly baffled and a bit annoyed by the whole situation (sorry), but however frustrated they were, our feelings were multiplied a thousandfold. Weeks and months passed with no clear progress towards release. This, combined with some world events of minor note (global pandemic), sucked ass.

A specific moment that extremely took the wind out of our sails was in late 2019, during that year's rendition of Melbourne International Games Week. We were already burnt out from the constant uncertainty around the game's release window, but were very strongly hoping to be able to release that week. Our bad feelings from burnout were somewhat offset by our three nominations (art, narrative, music) at the Australian Game Developer Awards; we were up against Untitled Goose Game, so we knew we wouldn't get Game of the Year, but we were fairly confident of picking up something.

That was until we were unceremoniously disqualified from the awards two nights before the event. Necrobarista's game director was pulled aside at an industry party and given the news by one of the organisers - the reasoning given was that we hadn't yet released, so we were no longer eligible. To rub salt in the wound, we received an email the next day via the nominees mailing list claiming that the award trophies had been "received incomplete", which to us indicated some sort of last-minute change to the list of winners.

They didn't even refund the $30 entry fee, as far as I know. 🙁

Unsurprisingly, this was disastrous for morale. Our motivation disappeared alongside our hopes for a 2019 release. Work continued, but I think it is fair to say that a large part of the reason the game released at all is that Ryan, one of our programmers, worked tirelessly to tick every box for the certification process. He did not work alone, of course, but the word I would use to describe his contribution is "outsized". Thanks, Ryan.

So the game eventually released nine months after The Awards Debacle. The only highlight of this absolutely wretched development process was the excellent critical reception we enjoyed. Shipping a game about death and grief in the middle of a global pandemic is not something I would recommend, but it resonated strongly with players and reviewers. That's something I treasure. But for all the critical acclaim, the game just didn't sell enough. Our wishlist conversion rate was terrible, and we were all locked inside, so all we could do was watch the sales numbers flatline in real time. Around this point, I was working in the regrettably common and perennially underresourced role of "community manager who also does marketing", which meant that I was made to feel like the success of the game rested solely on my shoulders. This, combined with the lockdowns, was not a particularly happy time. Shocker.

A year after release, the game had sold roughly 29,000 copies on Steam.

The game passed 50,000 Steam units sold in 2024.

Beyond the positive reception, Necrobarista also received some respectful and appreciated criticism around its lack of Indigenous Australian representation. The lack of it is a difficult subject for me to tackle: I am of Indigenous descent myself, and my grandfather was from the Stolen Generations, so my inability to include that representation is something I personally regret. However, in reality, I struggle with connecting to and feeling valid within my culture (by explicit design of the colonial project!) and I was simply not given the resources by the studio to even begin to be able to ensure respectful representation, so I chose to avoid it. Additionally—and this is not to pass the buck, but to illuminate the process in its entirety—the game's director was not interested in representing Indigenous characters. In hindsight, I think I chose correctly, even considering the regrets I've been left with. It is incredibly important to consult deeply and respectfully with cultural stakeholders, and to have the entire creative team invested. It's essential to get it right. I don't think anything I could have done in my situation would have hit my personal standard for getting it right. Other games both before and after Necrobarista have made ill-informed attempts and gotten it disastrously wrong. That is worse, in my books.

(If I had it my way, I would prefer that people actually read Dakoda's piece and understand my personal context as a creative before thoughtlessly painting the game with the same brush as those other ones, but perhaps that's too much to ask.)

In the year or so after release, the team shipped two DLC episodes and some extra features and then released a final "director's cut" where the DLCs got essentially completely rewritten, and the main story got some edits too. It was a comfort to return to the writer role and go back and fix some⦾ things with the help of a very skilled editor/co-writer (thank you Saf), since it was absolutely not a possibility during development of the base game due to the frankly baffling way the game was architected. I'm not trying to throw shade at anyone for this one specifically, but in a nutshell the process of adding and removing shots or visual sequences from the game was extremely convoluted and often broke everything. It was not my job to do those things and I'm very glad it wasn't.

(Remember how I mentioned work kept being redone? This made it even worse.)

⦾ There ended up being a lot of text in the game that didn't meet my personal quality bar, whether for content or editing reasons. We improved and/or fixed as much as we could, but there wasn't enough time to do a pass over everything.

This, however, means that the process of rewriting anything from a single line to entire scenes or DLC episodes meant that we were doing the equivalent of rewriting an episode of TV without changing anything that happened onscreen. We had latitude to remove shots, but that was the full extent of our capabilities. It was a very complex process and I believe we worked wonders with what we had.

To return to a birds-eye view of the dev process: at various and multiple points during the above, most of us lost our minds a few times, and it was not especially flattering or elegant for anyone involved. None of this is particularly fun to recollect, because everything that happened had real human consequences. We just crashed out, in public and in private, because everything sucked and had sucked for a long time and there was no avenue to healthily process that - and most of those aren't my stories to tell.

But overall, looking back at my personal Final Pour postmortem four years later, the main thing I'm struck by is how much I was hurting. Life was not happy, for a lot of reasons, and the circumstances and dynamics at the studio were a large contributor to that. With a bit of distance, I'm more forgiving to myself. That's something I've learned: you get to choose the lessons you take away. I have very much learned, for example, to pick my battles, and to be more conscious of my own limits. Good takeaways, but I wish those lessons had come at less of a personal cost.

That's about all I can offer in terms of a satisfying ending to this. Is it immensely satisfying to hold a physical copy of a game I worked on that's playable on Nintendo Switch? Absolutely, that's bucket-list material right there. Is it kind of bullshit that I had to be gifted it by a friend⦾ instead of receiving a copy from the studio? Also a resounding yes. Was it worth working on for years on below-minimum wage? I don't have a good answer to that, and I don't know if I ever will. To assign personal narrative value to the hardship is natural - it is only human to try to make sense of it, to try to believe that it was worth it. I hope it was! I know it made a difference for some people, and that must be worth something.

⦾ Thank you, Ruqiyah, steadfast friend and developer of beloved "better than Necrobarista by objective metric of number of narrative AGDAs won" visual novel Amarantus

But to widen my scope a little: after thirteen mostly-extremely difficult years working in the games industry and ten mostly-empty months having passed since the conclusion of my last long-term gig, I'm asking myself a lot of questions around sustainability, to the point of actively exploring other career and study options for next year. I am watching senior devs get pushed out of the industry, and I am watching the ranks close around North American and European studios who were only just beginning to consider that talent exists outside of their spheres. I have always felt like I was on the margins, but now more than ever, with multiple job opportunities having appeared and then promptly evaporated on me this year, and also with the state of the games industry somehow getting immeasurably worse every single time I come back to edit this paragraph, hope is in short supply. Resources and opportunities were always scarce for someone living in South Australia, but they feel nonexistent now. So, unless things get a lot better for me by the end of this year, I'm going to have to make some very difficult choices.

It feels like the fire's gone out, and I'm just left here stirring the coals. It's unsatisfying from a narrative standpoint, but that's just the way it is.

Minutiae

As a postscript: in the year after release, I started initial explorations towards a semi-sequel to Necrobarista, set in the same universe, in the form of a low-fidelity (by modern standards) RPG along the lines of Persona 4 or YIIK. I thought it would be significantly more appealing to a wider audience than a visual novel (which are hard to sell!) and I made some pretty positive progress before it got killed off - the studio director wanted to attempt to get funding for something else. I don't know if that ever happened, but for me, that's the project that got away. Still think about it a lot. Ah well.

As a second postscript: here is the original version of a moment in Necrobarista's epilogue. It was cut down for budget reasons.

As a third, final postscript, to elaborate on the second: I find it valuable to share original, internal documentation when I can. I did it with the Grim Tranquility script that I was brought in to do script doctor work on, and I will do it with Necrobarista too. So, here are the scripts for the original 2020 release, all ~194 pages, with original comments. I hope someone finds them valuable or interesting. If you do, let me know! I'm happy to chat about pretty much anything.

Reader Questions

Natalie asks: "What is something about writing that you learned in the process of Necrobarista's development and wish you would've known at the start?"

I've covered this above to an extent, but it's worth saying twice: I wish I'd known that writing doesn't have to be a painful, extractive process. When you're young and blessed with limitless energy and cursed with a violent desire to match your peers and Achieve Great Things, it's too easy to start burning the candle at both ends. I spent 2019-2022 suffering pretty severe burnout.

In terms of things I learned: I love collaboration! I love working together to fix story bits and punch up dialogue. That friendly, safe dynamic was generally absent for the majority of Necrobarista's development, and only appeared once Saf joined me to start rewriting the DLC episodes (Devil's Den and Walking to the Sky). For example, the Walking to the Sky DLC rewrite process essentially consisted of us writing jokes in a spreadsheet at each other. Not a lot of people played those DLCs, but those who did have enjoyed them a ton.

Caroline asks: "What was your favorite part of the story to write? Or a part that really vibed with you?"

I think I got the most satisfaction out of the Ashling intermissions and the fourth act - basically everything after the resurrection ritual fails. Writing a bunch of people dealing with a horrible situation in unique ways plays to my strengths as a writer (see: both Laen and the Axle in Eternal Strands), and it was a part of the creative journey where I felt all the seeds I'd planted were beginning to bloom.

Fia asks: "Is there a part you feel particularly proud of, and if so, what led you to making that part?"

This is a more specific version of my last answer: the sequence where Maddy and Chay sit at his gravestone, talking around the problem, delaying the inevitable? Banger, if I do say so myself. Watching people react to that specific part reminds me that I'm actually pretty decent at my craft - that final moment wouldn't have the impact it does without the benefit of a ton of very strong characterisation beforehand.

I knew from the beginning that there'd be some sort of scene along those lines, though the specifics weren't nailed down until I sat down and wrote it. I chose to keep the scope for the scene extremely constrained: two characters, one location, as few animations as possible. Everyone else had already had their chance to say goodbye to Chay in their own way, and given Maddy's avoidant personality, it fit perfectly that she would be the last one to accept his fate. Weaving together that sort of narrative payoff is always a great moment.

Sahil asks: "Who was your favourite character to write?"

This is a genuinely tricky one to answer, because I got something different out of writing each of the characters - they're all special to me. I'll twist the question a little: my favourite relationships to write (by a small margin!) were Ned's relationships with Chay and Kishan. I've written on this before, but there's little to no representation in videogames of friendships between Australian men. There tends to be a certain respectful stoicism in these relationships, characterised by quiet acts of service. When Ned is sitting outside the cafe with Kishan and offers him a cigarette, that is a layered and meaningful interaction that might be invisible to someone outside of the Australian cultural context. Likewise, Ned is heartbroken about Chay's death (they might be former lovers! maybe!!), but in lieu of an emotional response, he instead starts gently bending the Council of Death's rules for Maddy in hopes that her illegal ritual might indeed bring Chay back to life. There are hidden layers of respect and care in his choices and actions, all laid with explicit intent on my part.

Milo asks: "Have you been able to look back on your work in the game in-and-of-itself and appreciate it, or is your view on it permanently coloured by the conditions/dev process etc.?"

Absolutely. Even if times were frequently bad, I'm confident that I was one of the only people who could pull off the task of writing the game, particularly in regards to nailing the Australian cultural authenticity and specificity (which was lacking prior to my joining the team). I'm proud of that achievement, and I always will be.

Mads says: "Any thoughts about creating a sense of 'Melbourne-ness' in the game would be interesting! I return to your piece about Australian culture in games a lot and I think that further layer of specific localism in Necrobarista was intriguing too for a lot of reasons."

It was extremely important to the team for Necrobarista to be a Melbourne Videogame, so it's ironic that someone from Adelaide ended up in charge of the narrative. Locals will understand.

I consider myself very lucky to be relatively well-travelled. I've lived in several places across both Australia and the United States, and I've been lucky enough to travel beyond that, too. That's given me a slightly wider perspective on the world and in particular a good understanding of what a place like Melbourne has in terms of cultural differences with the rest of the world and the rest of Australia. Australia itself, of course, is not a cultural monolith, and given that it is a young nation where its denizens often define our identities in a way that centres our differences to each other, it's important to keep that in mind.

Taking that into account, there was already a ton of Melbourne influence in the visual aesthetic of the studio's earlier prototypes, though that influence was mostly absent in their narrative aspects. The "tram demo" was set on a tram (wow!) and featured Ned in a design very similar to his appearance in Necrobarista. Similarly, the Project Ven prototype was set on a rooftop cafe in a place that looks a bit like Melbourne.

As I mentioned before, though, the narrative throughline of Australian culture was missing prior to my arrival. The project had not employed an Australian writer, and it showed.

Anyway, Melbourne to me is the following:

- The densest urban environment in Australia.

- An extremely racially and culturally diverse place, by Australian standards.

- A highly competitive cultural and business environment that feeds into itself, ouroboros-like, in a way that has historically choked out cultural power from other parts of Australia.

- This is an intentional cultural strategy from the Victorian government that has, among other things, stifled the recovery/re-growth of the game development industry in Australia following the 2008 financial crisis.

- Which is to say: Melbourne is a place that has developed a culture of believing that it has the best of everything that any place could offer (like coffee), and that it's simply not worth considering that other places might have nice things too.

- That's why Maddy makes that off-hand crack about getting teleported to Adelaide, because that's the worst thing a Melbourne-dweller could imagine.

That might sound pretty snarky! But having just a tiny bit of a wider perspective and set of experiences means that I was able to work with the project's existing aesthetic touchpoints (coffee, trams, Ned Kelly, alleyways, train stations, repurposed industrial buildings) to build a story that felt authentic. Ned, for example, doesn't work as a character without the internal contradictions he faces of being a famous criminal and working-class hero but having been pressed into the service of the Council of Death, becoming a part of what he understands to be an oppressive system. And the cafe environment itself doesn't work without extensive experience of both Australian cafe culture and Australian people culture. You can't just throw together aesthetic influences and assume it'll come together - you need to have enough lived experience to breathe life into every aspect of the work.

(Fun fact: the first time Starbucks tried to expand to Australia, it failed miserably.)

That said: with the benefit of hindsight, I wish we had been able to do better to present a more specific Melbourne space. It's reasonable to say that perhaps the anime influences shone through a little too brightly in the environment design - I would have liked the train platform in Walking to the Sky to have more specific environmental hallmarks, for example. But, in truth, I don't think the team could have done any better under the specific constraints that dogged this project. It's so easy to compare Necrobarista to its contemporaries, but we were working under an incredibly small budget. Perhaps more experienced and competent studio leadership would have made better choices around sources of funding and choices of publishers, but that's all theoretical at this point.

What is heartening to see, though, is other narrative-focused games that came after Necrobarista that have aimed for similar kinds of locational and cultural specificity. Necrobarista wasn't even close to being the first game to do this, so I'm not going to be arrogant and assume that we inspired that, but it's good for it to have been part of that conversation, and I hope we get to see more in the future.

I'm happy to expand this section with further answers - feel free to contact me with questions and I'll do my best!